Jhe Russell’s heavy plastic cleaning cart wobbles as he pushes it across the uneven brick walkways of Iowa City. Every bump sends broom handles and bottles clattering like loose bones. The cart’s color is stop sign red, with the message “I love this place” stamped around the exterior. The scent of peroxide from his clear plastic spray bottles fills the air. It’s just past 7 a.m., the sun barely warming the metal grabber he uses to snag loose wrappers. Russell waves to a man sleeping on a bench, then nods and grins at two students walking by. He knows almost everyone. The regulars, the drifters, the business owners. Out here he feels comfortable.

“These are my people,” he yells, arms outstretched. “This is my city!”

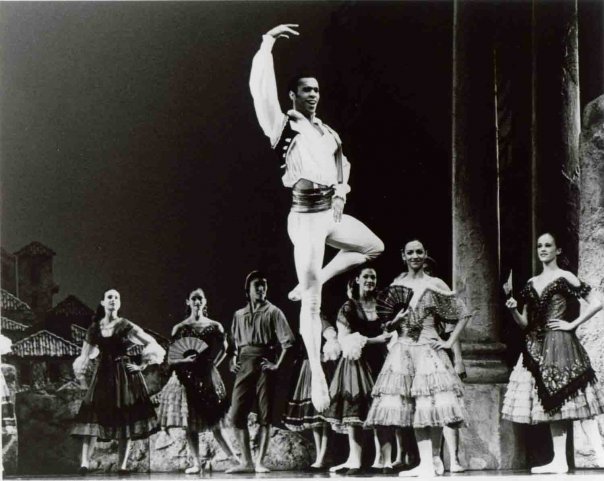

Russell dons a black-and-red winter coat. He neatly tucks his oversized black work polo into his black company pants. The logo of his company, Block by Block, is stitched on the front of his jacket. The organization, hired in June of 2024 to manage Iowa City’s Downtown Ambassador Program, aims to keep the streets clean, welcoming, and safe. Russell is a big part of this program. Whenever he spots trash on the ground, it’s time to do his job. He bends down with a practiced grace, his left leg kicking back in that same slow rhythm it’s had ever since it started giving him trouble. People rush past without a second glance. They see him as little more than a garbage man. A barrier on their way to work, a smiling interference in their normal walk to class. They don’t know his rhythm once belonged somewhere else. Decades ago, the 49-year-old performed ballet on stages in Romania, Canada, and Switzerland. But the chaos of life’s winding path brought him to Iowa City. This cleaning cart. These streets. And a purpose those strangers could never imagine.

When it was good, it was extraordinary.

Russell won major international recognition, including first place at the Erik Bruhn Competition in 1999 and a cover appearance in The Dance Current that same year. He trained at elite institutions like the Boston Ballet School and the National Ballet School of Canada, later dancing lead roles with world‑renowned companies. At five years old, Russell entered ballet because he wanted to fly like Superman. His childhood hero. And for years, he did just that, reaching the peak many dancers only imagine. But ballet demands perfection. And perfection demands endurance.

“You always want more,” said Eloy Barragan, professor of ballet at Iowa. “Sometimes, it’s a nightmare. And when you get injured? It’s Hell.”

Russell’s body began to break. A torn ACL. A cadaver knee. Double-digit sprained ankles that never healed. Two left shoulder surgeries—the nail in the coffin, as he puts it. Those are just the ones he remembers. Still, he couldn’t take a break.

“When you’re a dancer, you better shut up and take your Advil,” Russell said. “You’ve got a matinee tomorrow. You better get that review.”

So the performances continued. And the pace didn’t slow. At 22 years old, while dancing in Canada, he found a way to keep up. Russell was snorting two eight-balls of cocaine a day—roughly seven grams—while still dancing, still being cast, still winning. At first, he said, it was euphoric. The snowy seduction felt endless. But in using it over and over, he lost his passion for the art altogether.

Russell remembers one day where he woke up to birds chirping outside his dormitory window in Canada. He had a beautiful woman lying beside him in bed. He used to dream of this moment. And yet he couldn’t help but hate the life he was living.

“Fuck it,” he thought to himself. “I’m just going to overdose one day. Who cares?”

There’s a lot that goes into a name. Some carry history, others are simply chosen from baby-books. Jhe’s name was supposed to carry his father’s. John Henry Evans. Only Jhe didn’t really know his father.

“I met him one time and he was a robot,” Russell said. “He was basically just child support.”

And after his father disowned him later in life, Jhe reclaimed it. Now, he says it stands for something else entirely: “Just hug everyone.”

Jhe strives to live out that statement. As he keeps on pushing his cart, he sees an old friend.

“Whaddup J.D.!”

The two of them hug.

“Whaddup Jhe,” he mumbles back.

J.D. is a large black homeless man, carrying a half-smoked cigarette in his right hand and a black trash bag full of belongings in his left. He’s wearing a gray Hawkeye wrestling hoodie, heavily stained tan pants, and neon orange and black shoes. Most people will avoid J.D. His schizophrenia and spells of erratic yelling normally force others to take a detour. Jhe doesn’t pass him.

“I’ve been where he’s been,” Russell said. “It sucks to feel invisible.”

Right now, they’re both the opposite. They’re both present. And even as J.D. imaginatively rambles about his past lives as an NFL player and husband of a supermodel, Jhe listens. And smiles. This is what the job gives him.

“We’ve got to get on now,” Russell says. “Stay grateful brother!”

“Peace, Jhe.”

It was 2014, and Russell was about to perform for a legend. But he wasn’t dancing, he was speaking. He sat on a couch with his hero, 79-year-old Raven Wilkinson, widely recognized as the first African-American woman to dance with a major classical ballet company. Russell had tracked her down through Alonzo King, director of LINES Ballet. He had written a song for her, mailed it on a CD, and after hours on the phone, they finally arranged to meet.

Wilkinson had endured relentless racism in the Deep South. Crosses were burned in front of her, the KKK threatened her, and she was even urged to paint her face white before shows. She always refused. Russell had long admired her strength. But now, that strength looked different. Frail and shriveled by lung disease, she wheezed with every word. Yet she listened as Russell recited his poem. His voice shook with reverence as he spoke the lines he had written just for her.

“Hush little baby, don’t you cry, this little black bird is still gonna fly.”

Though written for Wilkinson, the line seemed two-sided, a reminder to Russell himself that he could still soar after years of struggle and trauma. And Wilkinson was a reminder that he could. She was no longer a dancer. Her own body was shutting down. That struggle felt painfully familiar. But Russell realized through their conversation that her worth wasn’t defined by applause or titles or perfection. Maybe his life didn’t have to be measured that way either.

Two years after their meeting, now retired from dance, Russell choreographed a tribute child ballet titled Birds of Light. Another ode to his hero. To Raven. The woman who made him appreciate life beyond the stage lights.

“Because of her, I woke up,” Russell said. “When I saw Raven, I got a different kind of inspiration.”

Outside of work, Russell’s world is small. He doesn’t keep many people close. Mostly, it’s just him and one friend: Jenni Rose.

They met years ago at the New Pioneer Co-op, when Russell worked as a cashier. Rose, who also walks with a limp, noticed that Russell was allowed to sit on the job, something she wasn’t used to seeing in her own workplaces. When they finally started talking, the surprise turned into recognition. Both had lived in bodies that didn’t always cooperate. Both had spent years feeling out of place.

“We live in a world where we’re starving for connection,” Rose said. “Jhe helped me embrace what I had.”

Now, they walk together around College Green Park, matching limps and shared ease. A couple of years ago, they even taught dance lessons together, drawing crowds of nearly fifteen people. Proof that movement is still theirs, even if it looks different than it used to.

“I’m still dancing,” Russell said. “I’m just dancing a little differently now.”

He often passes along lessons like those, the ones he learned from Raven Wilkinson. Reminders that the body is just one part of who they are, and that the world’s narrow definitions shouldn’t shrink their creativity.

“It’s rare to see people as free as he expresses himself in public,” Rose said. “You can tell when someone has lost their childlike wonder as an adult. But he still has it.”

And he displays that wonder everywhere he goes.

After the lunch break, which features a meat-free burrito from Estella’s and nonstop conversation with those behind the counter, Russell makes his way to the Downtown District office, the largest sponsor of Block by Block in Iowa City. A year and a half ago, the two companies joined forces, ensuring a clean and welcoming downtown atmosphere year-round. Russell wants to go in and thank them.

He parks his cart outside, and walks through the double glass doors. He limps up the three speckled-gray steps, and into a small elevator. His pointer finger, which protrudes through a hole in his black wool glove, presses the button to floor two.

There, Joe Reilly awaits. Reilly is the District’s director of operations, and runs into Russell frequently.

“He is the most standout ambassador we have in this city,” Reilly said. “Everybody should get to know him.”

If you’re not quick enough, though, Russell gets to know you first. His smile, featuring a partially overlapping front tooth, is always plastered on his face. And while he works five days of eight long hours each, changing trash and scrubbing phallic graffiti art, Russell consistently makes time to welcome everybody with open arms.

“If he could leave the cleaning part behind and just help the people, he would,” said Iowa City Block by Block Operations Manager Keyon Shelby. “We call him Mr. Hospitality.”

None of this is glamorous work. Not the aching body, the puke pickup, or the $19 an hour that helps him get by. But he hardly discusses money at all. He laughs when it’s brought up. For Russell, there’s a purpose beyond the paycheck.

“People often leave their high-paying jobs because they’re not being fed,” Reilly said. “Jhe is being fed here.”

The back sole of Russell’s left shoe is starting to wither. Black Nike Vapor Max sneakers, size 12, and well worn. Whenever he walks, that left foot swivels outward at a 45 degree angle, dragging through a small half-circle with each step. Sometimes his heel even skims the concrete, leaving a trail of scrapes on his sneakers. The motion repeats all day long, and not by choice. After torn ligaments and fused bones, his hip no longer rotates the way it should. Russell has learned to move around those limits, the same way he’s learned to move around so much of his past.

As he makes his way down a sloping sidewalk, he stops to pull over. Physically, that means guiding himself and his cart to the edge for a breather. Mentally, it’s a chance to pull his mind away from the pain, away from the rush of memories that flare with each twinge.

“When you’re broken nobody wants you,” Russell says, pulling from past trauma.

For the first time today, he isn’t smiling.

“I’m not just a body.”

A singular teardrop escapes Russell’s left eye, rolling down his cheek and tracing its way through the maze of his scruffy beard and skin tags. It glistens against his black skin. After keeping his eyes closed for so long, he normally sheds a tear or two when he lets the light back in. Not to worry, he says it’s normal. And it’s also spiritual. Before work starts each morning, outside his company’s office, he talks to the moon. Today, he’s rapping.

“This is Block by Block, trash talk that talk,” Russell rhymes. “We make it clean everywhere that you walk.”

That’s just one line of an entire song lasting two minutes and 24 seconds. Russell wrote the whole thing by himself. Rap has always been a big part of his life, and seven months ago his company shared this specific one on their main social media pages, tagging it as their “song of the summer.” Russell is forever proud of it.

The black metal bench he’s sitting on is cold, the handles littered with peeling rust. Russell grips them as he rhymes. Amber-scented cologne, which he rolls on his neck and wrist, wafts through the morning air. His posture is pristine. This is Russell’s routine. And though it’s the same concept, the blueprint often changes. Sometimes he’ll be sitting outside a minute earlier. Sometimes he freestyles, sewing words together rhythmically from the depths of his brain. There’s no real structure. That’s why he enjoys it.

In this moment, perfection doesn’t exist.

The cleaning cart feels heavier now, mounds of trash pile high in his “brute,” as the staff calls it. Russell wheels it around the corner, under a dimly-lit parking garage, and toward a cinderblock shed where other carts and cleaning supplies wait. Fresh blue towels, peroxide bottles, and cans of anti-graffiti spray line the shelves. Russell leans into the brute, organizing it for tomorrow.

“This is my least favorite part of the job,” he says.

It’s not because he has to clean again. He’s done that all day with ease. For eight hours, he’s been present, moving through the city that welcomes him. He’s fist-bumped the homeless, tipped his cap to young families, and smiled despite the shadows of his past. Even when others look down on his work, he doesn’t. This job gives him purpose.

No, what he struggles with is going home. Taking off the uniform and losing the feeling of a city superhero. Returning to who he was before the day began. Before he walked the streets that embraced him, a home he’s never quite had until now.