The first time I witnessed traditional Japanese music in the flesh was in a pyramid-shaped shopping mall in Aomori when I was sixteen. It was during a two-week long trip with my grandparents through Northern Japan, the first trip where it was just the three of us.

In this strange mall/visitor’s center that we stopped by, I found a bespectacled man in his fifties, his hair in grey spikes, sitting on a folding chair in front of a row of red, glowing goldfish lanterns, with a shamisen on his lap. Within a minute he shut his eyes and tucked in his lips, and began to play.

I joined the small crowd sitting in front of him, soon to become transfixed. I completely forgot about my grandparents, whom I had abandoned at that point, and gaped at the storm of sounds that he plucked, snapped, and strummed out of this one instrument. My amazement may be comparable to what people felt when Technicolor first came out. And so this random old man made me fall in love with the Tsugaru shamisen.

Generically speaking, the shamisen is one of the better known Japanese traditional instruments, aside from the koto or the shakuhachi. People often see it played in some sort of ensemble with the koto, shakuhachi, and maybe a taiko drum or two. You

Photo via kusuyama

sometimes have a group of shamisen players with drummers and flutists, who perform nagauta, a style of music, often accompanying narration, that originated with kabuki theater.

But it is more often than not played solo–even here you find a lot of variation.

A little about the shamisen family in Japan—the mainland shamisen has an uncle in Okinawa, called a sanshin (三線). It has a smaller, rounded body and slender neck, characterized by it’s warm, twangy sound. Think “tropical banjo.”

via ryukyu life

The sanshin has a number of nephews on the mainland. One oddball, which originates in Kyushu in southern Japan, is called the gottan—it’s basically a naked shamisen, consisting only of wood and the usual three strings.

The rest of the mainland shamisen are pretty similar, all having a square face and longer neck, played with a fan-shaped pick, or bachi. The relative thickness of the neck varies between thick, narrow, and in-between, depending on which type of music you are playing.

photo via pinterest

The Tsugaru shamisen, named after its home of Tsugaru (present-day Aomori), is one of these thicker versions. The sound is earthy and sinewy, unlike the more liquid, ethereal tones of its shamisen siblings.

It sounds as if someone decided to twist air molecules into strings and pound on them with a paddle. It’s reminiscent of moist dirt, dusty sunshine, grassy fields, and the midday ocean all at once, to the point that I can feel the scene like a film on my skin.

This earthiness/physicality also bleeds into the style. In a word, it’s violent—not what you generally expect with Japanese traditional music. When I watched this guy in Aomori play, I couldn’t close my eyes and relax for fear that at some point he would break all three strings or punch a hole in the shamisen (and I didn’t want to miss that moment).

While the left hand skates, leaps, and tap dances along the bridge, the right hand dexterously plucks and slaps both the strings and the surface of the shamisen with the bachi. Yet some of them do it with such force that you wonder if they have a score to settle with the shamisen. It’s as much a performative art as it is a listening art.

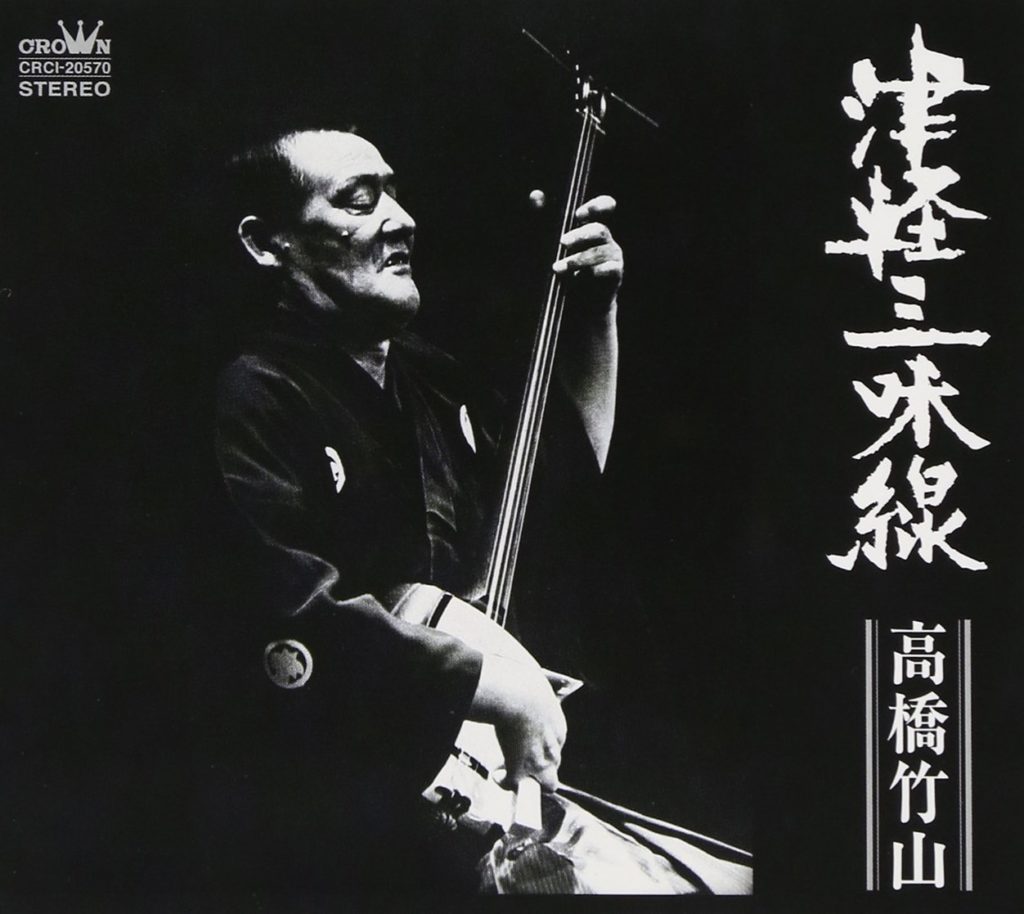

photo via amazon

I may also like the Tsugaru style, because it’s a lot like jazz. It sounds nothing like jazz—but it’s also a product of improvisation within a set of conventions. The players have no sheet music, but riff off these conventions to make the piece their own. Thus the same “song” will follow the same procedures, the same start and finish, but allows a very flexible middle section, where the players have free rein to do whatever they want as long as they want. It thus changes from person to person, like oral tradition, in the process accruing a human quality itself.

Here’s a video of a Tsugaru shamisen artist completely owning it.