Politeness. In Japan, you cannot escape it.

It is not accomplished by smiling, or shaking hands, or saying “cannot” instead of “can’t,” like the breezy way we accomplish politeness in America. Instead, daily interactions at your house, during commute, in stores, in restaurants, and everywhere else are steeped (or at least are supposed to be) in formality, politeness, and pleasantness.

The most notorious example of politeness in Japan is its linguistic manifestation—honorifics. Loosely referred to as keigo, honorifics are a type of special grammar used when talking to anyone other than your equals. By equals, I mean people your own age, most family members, extremely close friends, or whomever you have agreed to not use honorifics with.

Otherwise, use keigo—to strangers, senior coworkers or classmates, and anybody older than you, even by a year.

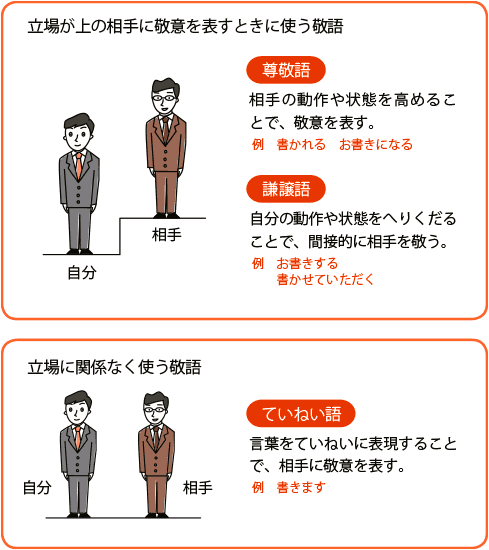

Think this is complicated? Keigo itself is divided into three main types, or functions—sonkeigo, kensongo, and teineigo.

Image via managementsupport (マネジメントサポート)

The first, sonkeigo, is used when talking or addressing someone “superior” to you. The word itself implies a verbally expressed reverence. When referring to yourself, you are supposed to use kensongo, “humble” language, the use of which elevates the addressee by lowering yourself.

Think of it as the teeter-totter of politeness. Teineigo, on the other hand, is a sweet middle, which does not change the stance of either speaker.

The information just relayed to you is akin to the statement that a car needs an engine, oil, and gas in order to run. In the event that you want to read further about honorifics, go here.

Politeness goes beyond honorifics and emerges elsewhere in daily social interactions. To give (a perhaps slightly ideal) example: go to your nearest convenience store and buy a pack of gum.

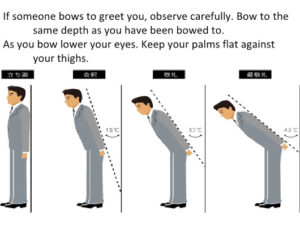

As you set your pack of gum on the cashier counter, you might notice how the clerk uses their hands—fingers stuck together, wrist bending at a delicate angle. You might also notice how they bow at least three times during the transaction—once when you first get there, once when

Image via Google Plus

you pay them, once again when they give you your change, and then a final time when you pick up your pack of gum and leave.

If you buy five packs of gum, you might see how they take the handles of the plastic bag, twist them, and with both hands swing the handles around so that they are facing you, ready to be picked up. The scenarios of politeness are many.

A footprint of the strict social hierarchy active for centuries, politeness and honorifics seem to be a reminder of the tentative divide between personal spaces, a sense of reciprocal debt between parties.

And yet, when someone treats you with perfect politeness but looks like they couldn’t care less about your existence, you wonder, “What’s the point?” Perhaps because of instances like these, some have asked whether Japanese politeness is insincere.

Rather than hop towards a general conclusion like this, it might be more accurate to say that

Image via Quora

because politeness is culturally essential, at moments like these, it seems to become a means and not an end, and the gap between word and action becomes that much more graphic.

Taking heed to the well-being and convenience of another member of society, as I have

noticed, is a mentality highly valued and cultivated in Japan, and politeness is an avenue towards this goal. But, as in any country, there are always exceptions to the rule.

And to label a country as insincerely polite flagrantly disregards the fact that a culture is still made up of individuals, people with a nationality in common but with individual beliefs, values, and quirks.

For further reading about the spirit behind politeness and its other manifestations, check out this article from the Japan Times.