It’s a phrase you might say when pulling into that familiar driveway of your childhood, or landing on the tarmac after a cramped eight-hour flight. Or something you might see on a small town’s rusty welcome sign. You hear it in Motley Crue’s famous song, “Home Sweet Home.”

Home sweet home.

But what exactly do we think of when we say, “Home sweet home”? Do we think of the house we grew up in, our hometown, or our home state? Perhaps it depends on where we’re coming from, and how far we go.

This familiar phrase has an equivalent word in Japanese—the noun 故郷, “furusato.” As opposed to its English cousin, it’s not something you whisper to yourself as you get off at your home train station, or walk into your parents’ house. Instead, it’s an interpersonal communication thing—while I think it’s pretty rare for Americans to ask each other, “What’s home sweet home for you?” It is a more doable thing in Japan. “What do you call your furusato?” “Do you have a furusato?” “I’m going back to my furusato.” Though used like “home,” it comes with the strong nostalgia and sense of belonging in “home sweet home.”

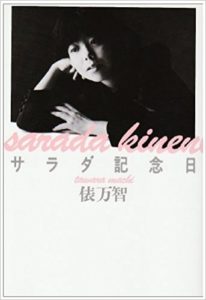

“Furusato” is also a popular theme in Japanese literature, music, and poetry. A couple of my favorite short poems (called “tanka”) about this topic are written by the author and poet Tawara Machi, popular for her book Salad Anniversary.

It feels like collapsing an umbrella

As I change trains

And find myself at home (from Te no Hira no Taiyou)

We smile about nothing

Laugh about nothing

Nothing really matters

That’s why I love my home (from Salad Anniversary)

Particularly with the second poem, it’s because Tawara Machi uses “furusato” that you can quite freely surmise that the speaker is a loooong way from home—which does not come out as well in my (feeble) translation.

A staple in children’s songs is, appropriately named, “Furusato,” with these wistful lyrics:

“Chasing rabbits up that mountain

Fishing for little carp in that stream

Even now those dreams come back

About my home that I can’t forget

…

If my wishes could come true

I would be going home someday

Home is where the blue mountains are

Home is where the streams are clear”

The word “furusato” is not without a little controversy, however. There tends to be a strong association of a rural setting with the word, which some areas in Japan have used for commercialization. In northern Japan, for instance, you’ll see haphazard billboard signs advertising the area as someone’s “furusato,” also hoping to lead you towards some ma and pa merchandise in the souvenir shop below the signs.

Regardless, this popular image has led to some interesting studies—one survey asked native Tokyoites if they considered Tokyo to be their furusato. Nearly fifty percent said that they did not. This was in stark contrast to the answers from people coming out of Tokyo, approximately eighty percent of which answered that they did have a furusato. Of course, there are Tokyoites who will fiercely insist that there is no reason to not call Tokyo their furusato—however, the rurality of the word still remains.

Yet we’re also in a setting where it was common for country dwellers to leave their rural homes to find work in Tokyo, to the point where this emigration to Tokyo also has its own word—joukyou. In this almost three-hundred-year-long pursuit of economic promise in the capital, “furusato” has become smoked with these flavors of long-distance exile and nostalgia, together with a stalwart sense of identity and attachment to one’s homeland. This also seems to speak to the individuality of Japan’s different prefectures—there’s now even a Furusato Festival in Tokyo every year, where you can go and get the unique experience of what Japan’s different prefectures, or should we say furusato’s, can offer.