Content warning: this article discusses racial profiling and acts of genocide.

The 1960s are often referenced as a time of liberation in American culture. Free love, drug use, and social movements including women’s liberation and civil rights for Black Americans dominate popular discussion of the 60s. However, during this time of widening freedom for many social groups, Native American women were facing renewed discrimination and violence by the U.S. government.

According to a 2005 study published in Wicazo Sa Review, “from the early to mid-1960s up to 1976, between 3,4002 and 70,0003 Native women—out of only 100,000 to 150,000 women of childbearing age— were coercively, forcibly, or unwittingly sterilized permanently by tubal ligation or hysterectomy.”

Dr. Connie Pinkerton-Uri, a doctor of Choctaw and Cherokee heritage, was the first to notice the pattern of forced sterilizations done by the Indian Health Services (IHS) system. In November of 1972, a 26 year old patient asked Dr. Pinkerton-Uri for a “womb transplant” because an IHS doctor had performed a hysterectomy on her when he diagnosed her with alcoholism. After seeing two other patients who were forced to undergo sterilization by the IHS, Dr. Pinkerton-Uri started to investigate.

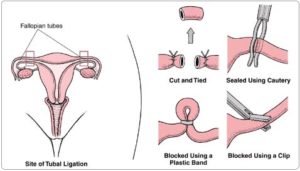

One tactic that the IHS routinely utilized was to sterilize women without their consent during other, unrelated surgical procedures. For example, performing a routine appendectomy and then also doing a tubal ligation without consent. According to the American Indian Quarterly in 2000, at least 25% of Native women between the ages of 15 through 45 were coercively sterilized during the 1970s. This is an overwhelming portion of the population.

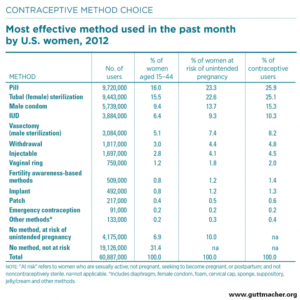

The Guttmacher Institute finds that today, 25.9% of women have undergone some type of sterilization surgery as their chosen method of contraception. For the rate of Native women who were forced to have a sterilization to be the same rate as the amount of women who haven chosen to have the procedure done demonstrates how far this systematic sterilization campaign went.

It is important to analyze this injustice in the broader context of the relationship between Native people and the United States government. Since the first Europeans came to the Americas, they have sought to manipulate and eventually exterminate Natives. This happened in many regions of the Americas — indigenous people in what is now Canada, the United States, Mexico, and Central and South American countries were all targeted and brutalized by European settlers. In this way, the violence of forced sterilization is nothing new and in fact only continues the history of genocide of Native people by the U.S. government; according to international law, targeting racial groups and trying to prevent them from giving birth is an act of genocide.

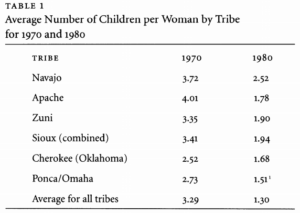

This has had a grave impact on Native communities. Dr. Pinkerton-Uri found that the IHS “singled out full-blooded Indian women for sterilization procedures.”, and had a larger initiative to reduce the birthrate of Native American tribes. From the 1970s to the 1980s, the birthrate among all Native tribes dropped drastically.

The impact of forced sterilization on individuals and communities cannot be overstated. It is one of the most violent ways that the state can destroy a person’s bodily autonomy. Because of the severity of this issue, I will be writing in later columns about other groups that have been targeted by the U.S. government, including Black and Latina women.

Genuine Justice is a column about reproductive justice focusing on current events, historical perspectives and systematic racism in women’s healthcare.