Do fish feel pain?

Well, yes, obviously. Fish have pain receptors like the ones found in humans, and when they are injured, they act how you’d expect an animal in pain to act.

But consider this: we’re not fish.

We don’t know what fish feel. What we can identify physiologically as pain in a fish’s body might not be expressed that way in their minds. Maybe fish pain feels different from human pain.

And consider this: maybe we don’t care.

Humans as a species have a reputation for treating other animals like playthings. We eat them en masse, experiment on them, dress them up and keep them as pets. We grind their bodies in large metal machines, keep them locked in cages and pens. We manipulate them as we see fit.

Maybe, to a fish, we are a race of uncaring, unfeeling gods.

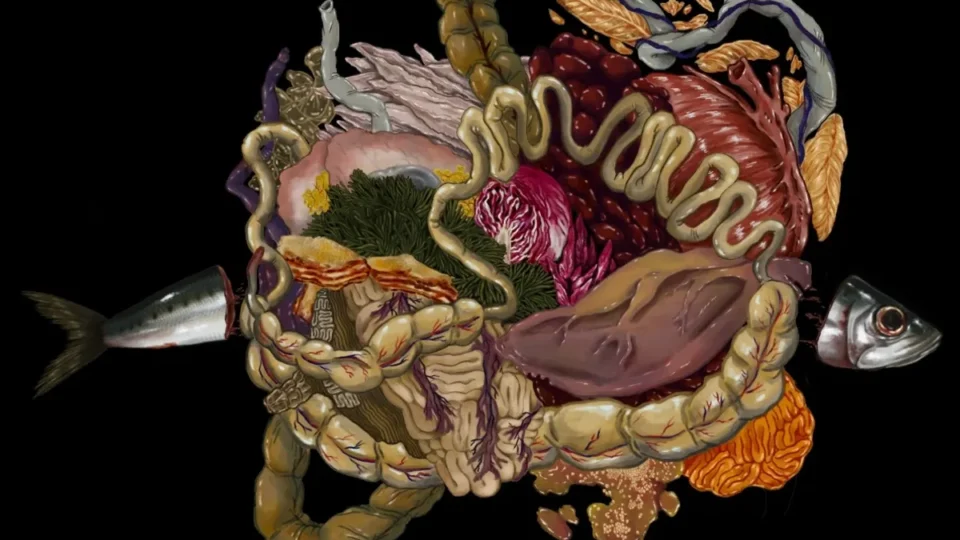

In How Fish is Made (2022, Wrong Organ), you play as, quite literally, a fish out of water who must make its way through a mysterious, pixelated landscape that walks the line between cold, unfeeling machine and graphic, fleshy human organ. As you traverse through the machine’s disgustingly rendered belly, you encounter other fish, who seem to have only one question for you: are you going UP or DOWN? You must answer every fish, but, interestingly, you can change your answer at will— the game doesn’t make you commit to your choice until the final room.

The mechanics of the game for the PC are relatively simple. You use your arrow keys to move forward and backward, your mouse to rotate, and the spacebar to interact with fish. It’s also a short game, clocking in at around 30-45 minutes to complete. But despite its simplicity, this game contains a surprising amount of depth. The environment, while pretty low-poly, evokes a visceral sense of discomfort and disgust through its depictions of disturbing body horror imagery. (The example that immediately comes to mind is the lotus seed pods, which have small, beady eyes instead of seeds.) And as you inch past your surroundings, your fishy flopping is accompanied by a score of mechanical whirs and fleshy squelches enough to make skin crawl.

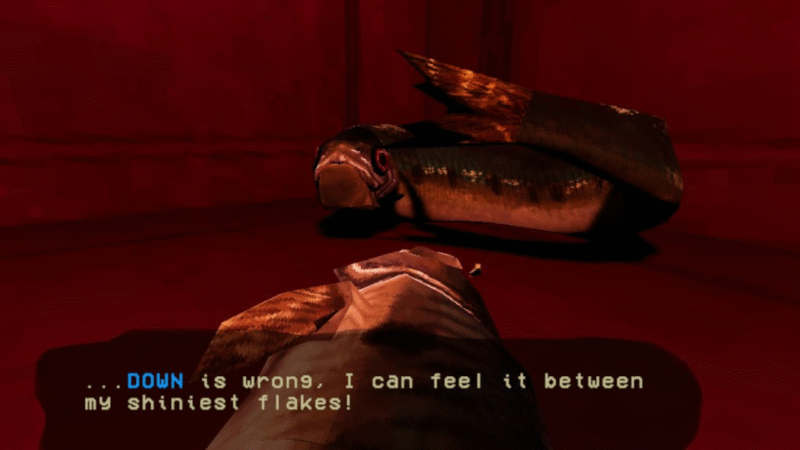

The game’s driving force is its NPCs: your fellow fish. When you first crash-land into the story, you meet a large fish who presents you with a choice — UP or DOWN — that will haunt you for the rest of the game. Every fish you meet afterwards will ask you the same question, but each one has a different perspective on the issue. One fish with a bent spine preaches the gospel of UP with a maniacal intensity, while another ensnared in a ring of plastic confidently declares that DOWN is the way to go. Some fish seem almost cartoonish in their convictions, while others act more human. A fish you meet will ask you whether they should travel UP with their family, or DOWN with their best friend. “I don’t want to choose,” they squeal, “if I can’t know exactly how it will turn out!”

At its core, How Fish Is Made breaks the human experience down to its most basic component: choice. And yet, when playing, you’ll notice that there are no humans in sight, only fish. However, there is a distinct human presence that remains unspoken. In one room, human voices play from distant recordings. The lights and buttons you find in the different rooms are fully functional, installed (presumably) by a human. In one of the most quietly disturbing moments of the game, you find one fish dead, trapped inside a condom filled with an unsavory white goo.

It’s interesting, then, that this game is about choice. As I mentioned before, humans typically remove most elements of choice from the life of a fish; we act almost like gods. So if humans are gods to fish, able to manipulate them at will, then perhaps the choices a fish makes in its lifetime are essentially meaningless. Whether it is eaten, used for testing, or kept as a pet, every fish ends up the same way: dead. Does it matter what the fish chooses to do in the meantime?

I fell in love with this game not because of its striking graphics, easy gameplay, or clever dialogue, but because of the way it considers the emptiness of choice. As soon as you are presented with the game’s central question — UP or DOWN? — you know that it doesn’t really matter which way you go. It’s not as if one path leads to death and the other salvation; this isn’t that type of game. You don’t get to choose if you die, you just get to choose how. You’re a fish.

In How Fish Is Made’s most memorable cutscene, a dancing parasite (I promise, this makes more sense in context) sings a song to you in front of pictures of decaying flesh and wriggling bugs. In the middle of his slideshow, he shows you a picture of a heap of dead fish in a cannery. On top, text reads: “Do Fish Feel Pain?” For the longest time, we humans didn’t think so, and we treated fish accordingly. But pain exists regardless of whether we perceive it or not.

When we picture a god of humans, we typically think of it as resembling ourselves. We draw them in human form, call them human names, and imagine that they understand human pain. But what if they can’t? What if the entities that control our fates, that make our choices virtually worthless, don’t understand the pain of deliberation that goes into making a decision? What if they exist only to use us while we live, harvest us when we die, and make our bodies into the filling of a delicious sandwich?

What if they don’t know — or don’t care — How Fish Is Made?

Stay tuned in with KRUI

Programming features, updates, special events, and more delivered right to you