The late 1990s was a magical time to be a young, naïve baseball fan. Every summer, multiple sluggers chased the single-season home run record of 61 and fell just short again and again. Finally, in 1998, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa burst through the barrier with 70 and 66 home runs, respectively. I still remember watching Big Mac’s 62nd live on T.V. Then the phone rang. It was one of my best friends. “Can you believe it?!” I couldn’t. It felt like a fairy-tale.

Roger Maris’s record that stood for 37 years would be surpassed four more times over the next three seasons, including a new record of 73 set by Barry Bonds in 2001. Something had changed. It may have been the fact that baseball players started looking less like Stan Musialand more like Steve Austin. Sure, all signs pointed to steroids, but the home runs were too exciting. Instead, we decided to take the Tinkerbell approach: clap if you believe.

At the same time all those home runs were being hit, Wall Street was playing around with its own Tinkerbell effect. Stocks nearly tripled from 1995-1998, averaging a 27.9% annual return. The investing public was in a state of euphoria summed up in a Paine Webber and Gallup Survey released in July 1999. Asked what they expected market returns to be over the next decade, those who had been in the market less than five years expected 22.6% per year. Sure, that had never been done before, but this time is different. You gotta believe!

Sensing a mass delusion that was bound to end like a night out on the Jersey Shore, Warren Buffett offered a sobering assessment in Fortune Magazine:

“Like Pavlov’s dog, these “investors” learn that when the bell rings — in this case, the one that opens the New York Stock Exchange at 9:30 a.m. — they get fed. Through this daily reinforcement, they become convinced that there is a God and that He wants them to get rich. Today, staring fixedly back at the road they just traveled, most investors have rosy expectations.”

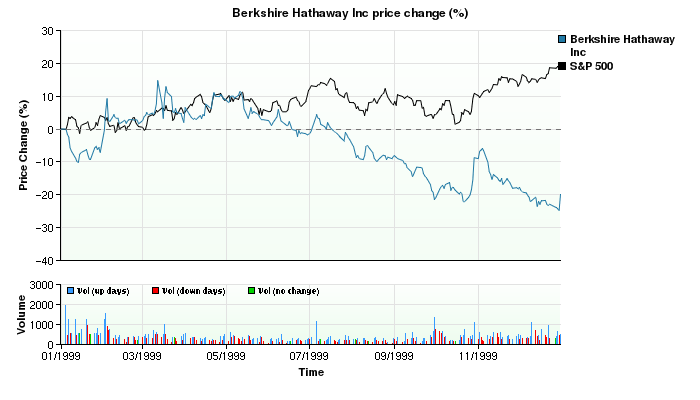

Now, some may call this a case of sour grapes. After all, 1999 was Buffett’s worst year relative to the market by a wide margin. Berkshire shares lost 19.9% in 1999 versus a gain of 21.0% by the S&P 500 as value investing fell out of favor and tech stocks were all the rage.

The reason for that underperformance was that Buffett famously sat out the tech bubble. He was well aware that the internet would revolutionize the country and the world (he was, after all, already close friends with Bill Gates), but he felt he didn’t have a clue which companies would come to dominate. It was simply outside his circle of competence and therefore not an investment choice he would consider.

The exuberant masses, on the other hand, bought indiscriminately and felt like geniuses as the bubble inflated further. To them, Buffett suggested they temper their expectations and learn the lessons of history.

After describing the two preceding 17-year periods (a bear market followed by a bull market), he warned of two other innovations that revolutionized the world but nevertheless produced poor investment results over the long run: automobiles and aviation. Among a couple thousand U.S. car manufacturers since the early 1900s only a handful remain. And they haven’t been particularly kind to investors. Buffett points out that as recently as 1992, the total combined profit of all U.S. airlines since the dawn of aviation was ZERO … literally zero dollars in total profits.

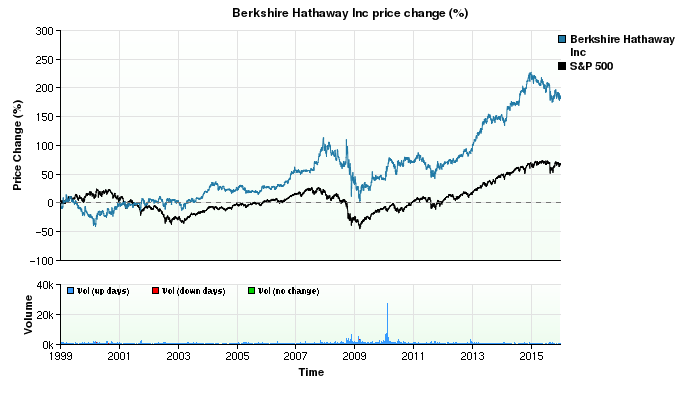

With all this in mind, Buffett sized up the situation he saw – below-average interest rates, sky-high valuations and corporate profits already being high as a percentage of GDP – and voiced his prediction of stock market returns over the next 17-year period: 6% per year.

Compared to the high hopes of 22% per year, this prediction made Buffett seem like the prudish bartender cutting the crowd off just as the party’s getting good. But as it turned out, even Buffett was too optimistic. From those nosebleed heights of 1999, the S&P 500 returned just 3.04% per year over the next 17 years, less than half the return of Berkshire shares.

Oh, and the home runs died down too. In the years since the Mitchell Report was released in December 2007, not a single player has hit more than 60 home runs in a season, and only four have hit more than 50. Fairy-tales can come true, it can happen to you. But if your path is unsustainable, the clock eventually strikes midnight.

Source: https://www.forex.academy